This post explores the rich metaphor of collaborative puzzle-solving to illuminate the dynamics of successful teamwork. By likening group efforts to the assembly of a jigsaw puzzle, we can uncover key principles that foster collective wisdom and creativity.

Collaborative puzzle-solving can be viewed as a dynamic process of Gestalt assimilation, where individual parts and the group as a whole continuously integrate new information and experiences into their learning mental models.

In this way, group sensemaking, decision-making and governance are involved in a dynamic 3-body problem team puzzle.

Collaborative puzzle-solving unfolds through several stages that can be viewed through an ordered yet recursive puzzle-solving framework. Various mental models act as modular frames that hold the filters and lenses that shape how we perceive, categorize and interpret the world.

1. Setting the Stage

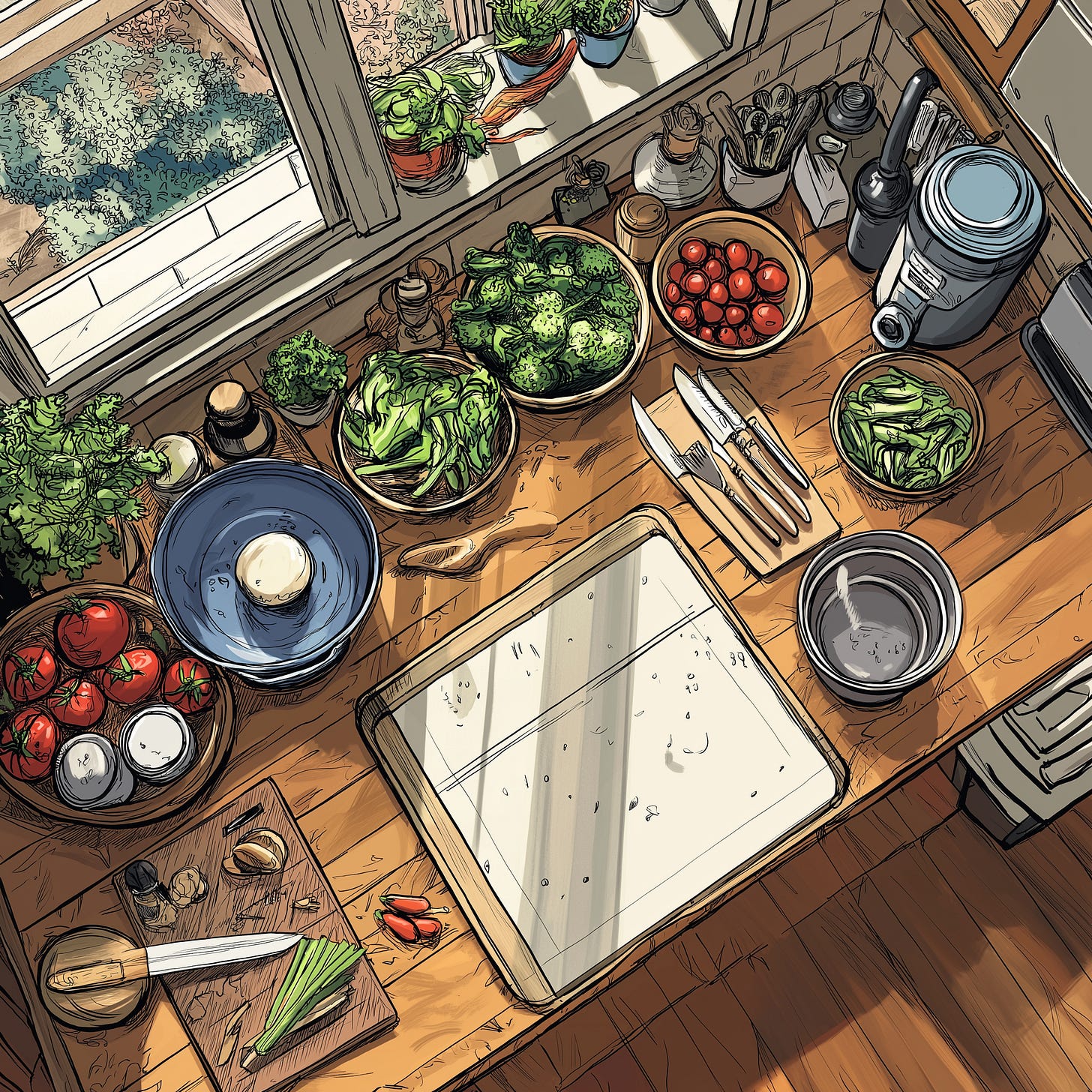

In puzzle-solving, the first task is to find or create a good puzzling area and surface. Just as a chef prepares their workspace with mise en place or a film director begins with the mise-en-scène, effective collaboration begins with intentional preparation.

Mise en place can be defined as the deliberate and organized preparation of the environment, peripheral objects, tools, and mental state to facilitate an immersive and effective puzzle-solving experience. Borrowed from the culinary world, where it means "everything in its place," mise en place here sets the stage for collective focus, flow, and creativity. This includes not only gathering the necessary resources but also clearing space and adopting a curiosity-first mindset. This combination of elements generates and cultivates psychological safety, where diverse perspectives are welcomed, held, and valued.

Alternatively, think of a surgical team in the operating room. First and foremost, the room must be meticulously cleaned, organized, and well-lit. Each member also brings specialized knowledge and skills. Their ability to seamlessly integrate their contributions within a safe, calm, and focused environment sets the stage for success. Similarly, creating an intentional and organized space for collaboration ensures the foundation for effective teamwork.

When ready, lay out all the pieces of your puzzle box on the table surface. Importantly, it is critical to work with all the pieces of the puzzle you wish to solve. Otherwise, you will eventually be frustrated: that one critical piece you were looking for might still be tucked away, hidden in darkness within the box. One can’t think outside the box if some of the pieces remain within it! The act of exposing the pieces—spreading them out for visibility—is akin to laying bare the scope of a problem or challenge.

“If I had an hour to save the world, I would spend 55 minutes defining the problem and only 5 minutes solving it” - Albert Einstein

Working with all the pieces requires them to be flipped and exposed, one by one, to the side showcasing the art. The art side is the most relevant, information-rich aspect of the puzzle at hand. This seemingly simple act mirrors the early stages of collaboration where participants bring forth their unique insights, strengths, and perspectives. Fostering an "ecology of mind1," as Gregory Bateson suggests, allows individual minds to interweave and create something greater than the sum of their parts.

In Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Bateson suggests that individual minds are interconnected and interdependent, forming a larger, unified system. Just as an ecosystem thrives on the diversity and interaction of its components, a collaborative team—composed among others of artists, scientists, investigators, crafters, citizens, and artisans—can benefit from the unique perspectives and skills that each member contributes. Emphasizing the interconnectedness of the team fosters a sense of shared responsibility and encourages collaboration, leading to more holistic and impactful creations.

Moreover, each puzzle piece holds unique characteristics and potential contributions to the whole. Or, as Rumi might put it: "In each drop, the ocean." This perspective reminds us that the strength of a collaborative effort lies not just in its collective achievement but in the recognition and integration of each individual’s value into the shared vision.

2. Sorting and Framing

We naturally approach problems with pre-existing mental models or frames. These frames enable the initial sorting of puzzle pieces and help us organize information to make sense of the task at hand. However, rigid adherence to these frames can limit our creativity and prevent us from seeing new possibilities. If a team clings too tightly to conventional approaches to a novel puzzle, they may miss out on innovative solutions.

Thus, puzzles offer us two key learning modalities among many:

Using and breaking frames.

Getting a grip on paradox.

During this stage, individuals apply pre-existing frames to categorize puzzle pieces. By frames, we mean perspectival lenses, type schemas, stances, orientations, mental models, and heuristics. Frames act as boundaries, defining the context and meaning of information. Common frames might initially be based on colour, shape, or other perceived patterns.

Stacked Affordance Frameworks

The following is a set of complementary, nested frameworks we can use to guide collaborative & transformational work experiences, whether as an individual, a team or whole community endeavour. These frameworks are meant to provide a minimum effective dose of structure in order to help coordinate and navigate through our landscape of travel, but also to create spaces for generative creativity.

Ultimately, we always start sorting with our most familiar frames. Ideally however, we should remain open to updating by letting go of initial frames and allowing shifts as the sorting process evolves.

The use of paradox can often be a way to shift, bend, or break rigid frames. Embracing paradox—the ability to hold seemingly contradictory ideas simultaneously—can help break our default frames and spark breakthroughs. In puzzles, as in paradoxes, opposites always coincide with one another. Observing the coincidence of opposites2 at your fingertips can be an effective way of "shaking the snow globe" and seeing the pieces from a fresh perspective.

For example, a puzzle piece may seem to fit in one place based on its shape, but its colour might suggest a different location altogether. Or you might find a straight edge, that doesn’t fit the outer boundary of the puzzle. What do you do with this information?

The subtle synthesis and creative manipulation of frames can lead to new insights and a more nuanced understanding of the problem.

The assimilation of frames can be further accelerated and made more effective through open dialogue about sorting criteria and coordinated collaboration. As Geoff Marlow discusses in The Five Fatal Habits, one key habit to avoid when solving puzzles is "One Best Way" thinking. Marlow suggests a shift to a curiosity-led 2D3D mindset3.

“None of us ever sees the whole 3D reality picture—which is why none of us is as smart as all of us.”

We all have blind spots. No one, no matter how brilliant, ever sees the whole picture in any real-world situation. Each of us only ever has a biased, partial, one-sided 2D take on a 3D reality. The good news is we can help each other out.

Thus, in a collaborative puzzle-solving mode, team members should be encouraged to share their perspectives on sorting criteria. Different individuals might see different patterns or relationships, enriching the collective understanding of the pieces. Collaborative puzzle-solving teams can actively share their unique perspectives, embrace constructive criticism, and strive for a collective understanding that transcends individual biases.

3. Experimentation and Fitness Testing

To find a fitting piece placement, solvers must engage meaningfully with a chosen piece and enter a sort of imaginal dialogue with it. This involves exploring its physical properties, imagining potential connections, and hypothesizing about its role in the larger whole. Donald Schön's notion of a "reflective conversation with the materials" captures this process beautifully4. This approach encourages experimentation, playfulness, and a willingness to let the materials guide the creative process. Engaging in a "conversation" with the puzzle pieces in a dynamic interplay of trial and error by exploring their possibilities and limitations allows for emergent discoveries and creative solutions.

When a team member selects a piece and hypothesizes its position, they are attempting to assimilate this piece into their developing mental model of the complete puzzle. They draw upon their understanding of the puzzle's overall structure, the existing pieces in place, and the characteristics of the chosen piece to imagine its fit. Another team member might have an entirely different "conversation" with the same piece, leading to diverse interpretations and potential solutions.

This live experimentation is essential for "deutero-learning”5. As Bateson discusses, deutero-learning isn’t just about acquiring new skills but also about developing the capacity to adapt and learn from experience. In other words, it is the key skill of learning to learn. Each attempt, whether successful or not, provides valuable feedback that informs future decisions and strategies. Each interaction with a piece informs future decisions and strategies through assimilation.

Deutero-learning is essential for a flourishing and aligned team focused on a beautiful, important goal. It encourages a culture of continuous improvement, experimentation, and reflection, enabling the team to evolve and create increasingly impactful experiences over time. Within this improvisational space, a "creative alliance" naturally emerges6. This alliance is built on trust, clear communication, and a shared understanding of the overall goals. It allows for individual expression while maintaining a cohesive direction.

Testing the fit of a piece in a collaborative puzzle requires a shared understanding of the puzzle's overall scope and guiding principles of success. The team must work together to determine whether the selected piece fits by intentionally designing a framework for collaboration that fosters alignment and synergy within the team. This involves establishing scalable terms of engagement and “letting go”, with respect to fit. In a jigsaw puzzle, the fit quality is typically obvious: the piece “fits like a glove,” or alternatively, there will be loose gaps or tight grinds. Beware! Some puzzles also have false fits. In those cases, other criteria (image/information continuity, piece reversibility) will need to be factored in.

A collective understanding of fitness requires a high level of trust and candour to establish a clear set of guiding principles that empower individuals while maintaining a cohesive, creative direction. A willingness to introspect and retrospect regularly can make the creative alliance all the more effective by developing collective proprioception: an acute awareness of its skills, capacity, experiential sensitivities, and preferences. By consciously cultivating a creative alliance, the team can enhance its collective creative potential and achieve a greater impact.

Once a creative alliance is unlocked, testing fit can be seen as a form of jazz band improvisation. Team members respond to each other's suggestions, adjusting their approaches and building upon previous attempts. The dynamic interplay and intuitive collaboration that characterizes a successful creative team is a joy to experience and witness. Each member, like a musician in a jazz band, brings their unique skills and sensibilities to the performance, responding dynamically and harmoniously to the contributions of others in real time.

Or, if you prefer, imagine a soccer team skilled in the art of Total Football7: each member understands their role and trusts their partners implicitly, allowing them to navigate challenging terrain with confidence and agility.

The best puzzle teams are those who practice solving regularly. Through routine practice, an intuitive felt touch and know-how can be developed (fingerspitzengefühl). Fingerspitzengefühl is a German term, literally meaning "fingertips feeling." It describes a great situational awareness and the ability to respond most appropriately and tactfully.

At the end of this stage, if the piece fits, the existing mental model of the puzzle is reinforced. If not, the team may need to accommodate a misfit and adjust their existing mental model to incorporate this new, contradictory information.

4. Adaptation and Integration

The puzzle-solving process inevitably involves encountering outliers and misfits—pieces that don't seem to belong. These misfits can be frustrating, but they also offer valuable opportunities for learning and growth. A team with a "living paradigm" embraces these challenges, adapting their understanding and refining their approach8.

This adaptability is crucial in navigating complex problems. For example, a scientific research team might encounter unexpected results that challenge their initial hypothesis. Rather than dismissing these findings as outliers, they can use them to revise their understanding and explore new avenues of inquiry.

Through fit and misfit, teams can step back, scale back, and make note of the puzzle environment, and context they are interacting within.

Ultimately, collaborative puzzle-solving is a transformative experience9. It not only leads to the completion of a project but also shapes our understanding, expands our perspectives, and strengthens our ability to work together effectively. By embracing the principles outlined in this framework, teams can unlock their collective potential and generate truly remarkable outcomes.

5. The Ever-Emergent Outcome

A successful Collaborative Puzzle-Solving Process is recognized by a coherent and cohesive team engaged in an effort towards a transformational experience. When the puzzle is solved, the team levels up. It should celebrate the win by reflecting on key learnings and savouring the sparks of success and the tiny miracles observed in achieving its collective mission.

As Claudia Dommaschk eloquently states:

"In terms of puzzling, I think of the moment when I drop the final piece in place: I step back and marvel at the finished ‘gestalt’. There is a pleasure, a satisfaction; both in the beauty of the final image but ALSO in having had the experience; both of which change me."

Well-designed puzzle-solving experiences thus embody the value and power of generative transformations. The process of assimilation involved in completing a puzzle extends beyond simply fitting pieces together; it shapes our understanding, expands our perspectives, and ultimately changes us. The satisfaction derived from completing a puzzle stems not only from the finished product but also from the journey of learning and the growth experienced along the way.

Steps to an Ecology of Mind, Gregory Bateson

The Coincidence of Opposites, Iain McGilchrist

Ways to fail at culture change, Geoff Marlow

Alignment beyond Agreement, Yasuhiko Genku Kimura

Leading Through: Activating the Soul, Heart, and Mind of Leadership, Kim B. Clark, Jonathan R. Clark & Erin E. Clark

Joe Pine’s Substack: Transformations Book.